My dear mama is so happy to see me and our closest friends, close enough now to touch us. I’m happy with simple acts like holding her hands, bringing her a drink of water, reading her a funny story from the latest copy of Catster… These things make us both happy, when you come down to it.

Last Thursday was Mental Health Awareness Day. To honor it, The Atlantic held a fascinating, day-long, online dive into The Pursuit of Happiness. (More about that in a minute.) That day, I both visited my Mom and considered some big Happiness questions. I’ve been thinking since then about the lenses through which we see happiness, both micro and macro.

Many years ago, I picked up a copy of Gretchen Rubin‘s The Happiness Project in an airport bookstore. (An aside… What is it about boarding an aircraft — especially on a long-haul leg — that makes some of us browse racks of inspiration and others head straight for the trashy, distracting novels carousel? I don’t know. Then again, I’ve been on plenty of flights where I just buy the local newspaper and a magazine I don’t subscribe to and leave it at that.)

In a much-needed attempt to improve my personal happiness quotient, I tried to follow Rubin’s practices. I made neat charts of actions to take, with squares in which to paste gold, blue or red stars. I even bought a roll of stars from Office Depot’s schoolteacher aisle. Each attempt lasted a couple of months, and then my enthusiasm for self-policing waned. I wanted to do the things that she promised would make me happier in the long run, but somehow, ticking good-girl boxes didn’t work for me. And so the efforts to improve fell by the wayside, even if they would have made me happier… Which was the whole point of her book.

Fast-forward ten years. (That alone shocked me. I have been picturing Rubin’s kids as toddlers and pre-schoolers for years. By now, I assume at least one of her children must be preparing to enter Yale Law.) Rubin was one of The Atlantic‘s speakers; she talked about her latest investigation into how humans are wired to behave. It wasn’t the only presentation to have me reflecting on the nature and creation of happiness.

We are better than we think

The day’s sessions roamed broadly through the realms of happiness research. Sessions drew upon the expertise of a dozen or more people, with diverse experiences. Speakers included Deepak Chopra and Vivek Murthy (America’s Surgeon General). Laurie Santos — the professor behind Yale’s insanely popular course The Science of Well-Being — and Jean Twenge, San Diego’s explicator of the iGen cohort. Mixed in with the interviews were snippets of the Dalai Lama. The Atlantic’s own Arthur Brooks popped in periodically to discuss concepts raised in his column, How to Build a Life. (Well, The Atlantic shares him with Harvard, but we get the idea.)

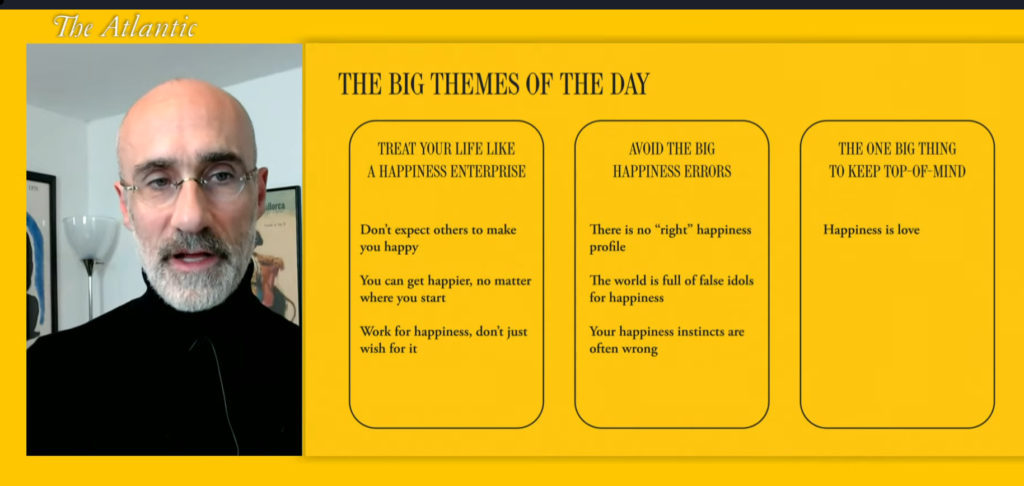

Famous though the other speakers were, Brooks’ ideas have stayed with me most clearly. I took this screenshot during his introduction to the day’s events:

Of course, when I look back at his first slide, “Treat Your Life Like a Happiness Enterprise,” I realize it leads off with a lesson I absorbed many years ago. Rubin herself stressed this point, in the context of cheering up her young child.

First, recognize I can’t make anyone feel happy. (What do you do, whack them about the head with a feather or a picture of a kitten until they laugh?) People inhabit their own emotions, for good or ill. Furthermore, if I can’t ‘do it’ to someone else, no one can make me feel happy, either.

Brooks went on to list “macronutrients of happiness” such as enjoyment, satisfaction and purpose, to help you serve up “dishes of happiness” to others. Those you might want to serve include your friends and your family, your partners in faith and at work.

How do I fit into the yellow boxes?

If we can’t make someone feel happy, why think there’s anything we can do to bring that person’s internal happiness quotient up a notch? What Brooks suggests is that we find some internal happiness macronutrients, and consider how we might serve them to friends, family and colleagues. Rubin says it a little differently, as I’ve noted before: Do good, feel good. And the beauty of this cycle is that when you feel good in yourself, you’re more likely to be generous, pleasant to others, willing to take the time to help someone who needs it.

What does this look like IRL, for me, I wondered? Here’s what I tried. How well do you think each idea worked?

- Mom was restless, fidgety, on my next visit. I decided to describe the AirBnBs I’m thinking of staying at in England as vividly as I could. I found something to connect each property to Mom’s own travels nearby. “Look, this place is walking distance to one of the first Roman villa excavations we ever visited! And Chichester! Here’s a photo of it in your memory book.” Before long, she was engrossed in the decision-making, nodding and laughing at my funny memories, as if she might venture to these places herself.

- I’ve been so nervous and uncomfortable visiting people this last year, even in the open air. Now I’m vaccinated, and they’re vaccinated, it’s time to re-engage with the world of friends beyond work colleagues. (Whom I’ve seen IRL because I dropped off moving boxes or Christmas presents from the safe distance of end-of-driveway…) I took a tour of a patio garden labored over by two dear old friends. Although by ‘patio,’ I mean rows of pots and plants on the scale of, oh maybe, Versailles. If Versailles had a crowded parking lot and was only 20′ x 20′. Later, I invited a colleague over to relax on a newly washed Adirondack chair, on newly mown grass, and drink — maskless! — a glass of wine.

- My colleagues, often stressed by pressures of time and clients of dubious temper, turn to me to solve problems as the clock ticks. No need to add to their sleepless nights by making faces at the laptop camera. I resolved to do my best to smile, make reassuring noises, show how we together can shave nanoseconds off their deadlines… and send them to play with their kids, spouses or pets a couple of hours earlier than they feared. Yes, I may work an hour or two longer to make it happen, but I live with far less domestic pressure than they do. Their relief — and consequent happiness — is ample reward.

And that’s what Arthur Brooks was talking about. Using my stock of macronutrients of happiness to serve a little joy where I can.