I believe there are three things particularly pernicious to the health of the body politic.

- Outright lies by politicians.

- Outright cheating at the ballot box.

- Efforts to stifle any citizen’s free access to the ballot box, outright or subtle.

Concerning the first: yeah, yeah, I know. Politicians have stretched the truth for eons. They puff up the benefits of their own programs or the sins of their opponents. But straight-up lies about facts are more than a disgrace to the liar. Take, for example, claiming the covid-19 vaccines are some sort of Democratic plot. Politicians suggesting people should distrust the science of vaccines puts their believers in harm’s way of serious illness. Indeed, Tennessee’s Republican lawmakers have taken anti-vaxx sentiments to extremes. They appear quite pleased at their success at thwarting all manner of vaccinations among Tennesseans. These politicians and their lies are also a hazard to a system of government built on trust and truth. Remember, the whole “we hold these truths to be self-evident” bit? The framers didn’t write ‘we hold our truths to be the only ones applicable…’

As for the second item, cheating at the polls. Thankfully, so far, most elections officials — from local administrators, through county auditors, to secretaries of state — have proved honest. They have conducted elections that are by and large scrupulously honest, and demonstrated (to the extreme annoyance of many Republicans, elected or lay-person) that their processes delivered accurate voting tallies. American voting machines and paper ballots are not without their faults. However, as a nation, we’ve avoided truly Third World box-stuffing tactics.

As for the third issue, ah, here the opportunities to wreak havoc on democracy are nearly boundless. Today, in honor of Elbridge Gerry’s birthday on July 17, let’s dig into gerrymandering and what the practice does to democracy.

Who was Elbridge Gerry, and why was an electoral trick named after him?

Elbridge Gerry was a real person. He served as vice president under James Madison. He also earns a place in constitutional history as one of three members of the Constitutional Congress who wouldn’t sign the document. His reason: it lacked a Bill of Rights. Gerry was also dubious about the direct election of the President. He advanced many proposals for indirect elections, most of which involved limiting the right to vote to the state governors and electors. (Yes, those same Electoral College folks that Trumpists sought to enlist to over-turn Biden’s election…)

He is far more notorious for signing into Massachusetts law a provision allowing the legislature to design partisan electoral districts.

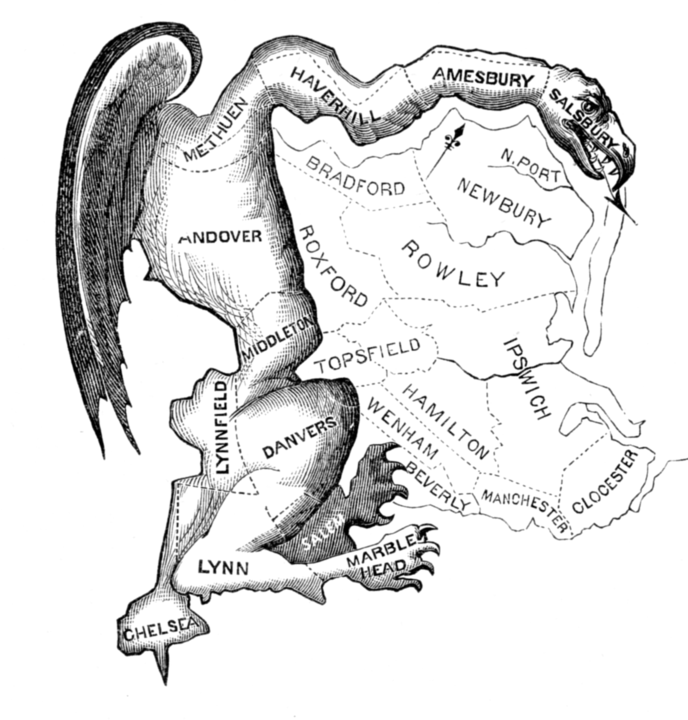

In 1812, the state adopted new constitutionally mandated electoral district boundaries. The Republican-controlled legislature had created district boundaries designed to enhance their party’s control over state and national offices, leading to some oddly shaped legislative districts.[83] Although Gerry was unhappy about the highly partisan districting (according to his son-in-law, he thought it “highly disagreeable”), he signed the legislation.

The Boston Herald laid the blame for the guarantee-my-seat districts right at Gerry’s feet.

The word “gerrymander” (originally written “Gerry-mander”) was used for the first time in the Boston Gazette newspaper on March 26, 1812.[79] Appearing with the term, and helping spread and sustain its popularity, was this political cartoon, which depicts a state senate district in Essex County as a strange animal with claws, wings and a dragon-type head, satirizing the district’s odd shape.

Modern-day gerrymandering

The Gerry-mander did not die out with the last Federalist. Indeed, the creature is alive and well in modern politics. But how does it work, you might ask? Well, common state-level redistricting criteria recommend that districts should generally be:

- Contiguous (meaning the boundary is solid, no skipping across some amount of land)

- Compact (constituents within a district should live as near to one another as practicable)

- Respect continuity of interests among constituents

- and, to some degree, respect community boundaries such as county or city lines

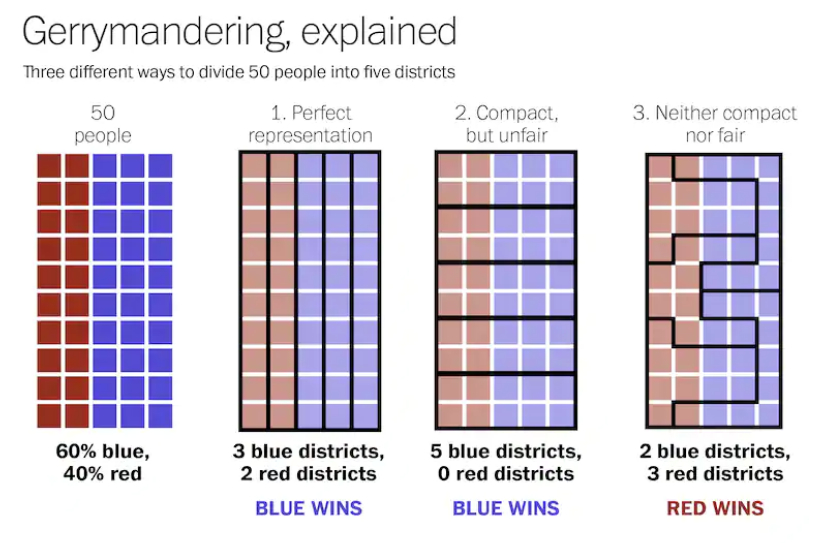

Let’s look at an illustration of three different electoral districts to see what fair vs. unfair districts look like. This illustration (from a 2015 article in the Washington Post, using an illustration drawn by Stephen Nass) shows how different district lines produce different results. Each meets the criteria of being contiguous, but that’s about it.

Clever, eh? Even if your party is in the minority, canny drawing of district lines can guarantee you win, even if your opponents have more registered voters than you do. You can effectively bar the majority from making decisions, by making it impossible for the majority’s party to hold offices that control decision-making.

Majority rule… it’s a thing. You could look it up.

Majority rule is, of course, the living definition of a functional democracy:

Majority rule is a way of organizing government where citizens freely make political decisions through voting for representatives. The representatives with the most votes then represent the will of the people through majority rule. Minority rights are rights that are guaranteed to everyone, even if they are not a part of the majority. These rights cannot be de eliminated by a majority vote. Minorities must trust that the majority will keep in mind the wishes of the minority when making decisions that affect everyone.

LawTeacher.com essay

On the other hand, gerrymandering is a very bad idea if you value having a healthy democracy. (By the way, did you notice the operative word “trust” in the last sentence of the quote? Now go back and re-read the first item in my list about the effects of lying to destroy trust in government.) In a healthy democracy, citizens feel confident that their votes will affect the composition of their legislature, and that as a result, policies they prefer will become law.

Voters in Washington, for example, have considerable reassurance about our district boundaries. A five-member, non-political commission draws district lines. Furthermore, our state constitution explicitly states that the redistricting commission “must not purposely draw plans to favor or discriminate against any political party or group”32.

What can I do if I suspect a salamander?

Not all states are so diligent. Some are downright naughty, appearing to draw electoral boundaries with the exuberance of a kid with a crayon. Beware! There is absolutely nothing random about these boundaries! Many Republican redistricting efforts are drawn with laser precision, using demographic software that makes Cambridge Analytica look like Leave was worked out on an abacus. In 2018, Wired noted:

Today, partisan lawmakers can use algorithms to design thousands of hypothetical district maps nearly instantaneously. With relatively few resources, they can then carefully predict how each layout might tip the scales in their favor, even adjusting house by house as needed. And since Republicans controlled a majority of state legislatures while redistricting took place after the 2010 census, those maps have skewed red.

Democrats have also attempted to gerrymander districts, Maryland perhaps most notably. But according to Princeton University in 2012, and confirmed by Mother Jones in 2013, gerrymandering is overwhelmingly a Republican sport. Business Insider noted the huge benefits Republicans gained by their actions, quoting AP: “…the data suggest that even if Democrats had turned out in larger numbers, their chances of substantial legislative gains were limited by gerrymandering.”

Some gerrymanderers have been dragged into court. However, in 2019, the Supreme Court decided your state has the right to draw district lines however it pleases, devil take the hindmost of voters. In other words, hard cheese if your party should win a majority of seats because it has the most registered voters, but doesn’t because the opposite party seized the chance to draw squiggly lines that are neither compact nor fair.

Protest and campaign for change

“If left unchecked, gerrymanders like the ones here may irreparably damage our system of government,” Justice Elana Kagan wrote in her scathing dissent. Even the libertarian Cato Institute has decried gerrymandering on the grounds of accountability and transparency. The author said, “The process feeds apathy. Residents who have not even figured out which district they are in are less likely to keep track of how well their representative is serving their interests.”

In recent years, partisan gerrymandering has become the target of citizen campaigns for fairer districts.

These campaigns take action at the local, county or state level to prevent or dismantle gerrymandered districts. While taking a legislature to court is one way, it’s a heavy lift for most anti-gerrymandering activists. A more effective strategy alerts local communities to their salamandered districts, taking the protest to the gerrymandering party by threatening to vote them out. Next month, we’ll take a closer look at their strategies. In the meanwhile, let this be your rallying cry:

Voters should choose legislators, not the other way around.